Before I get to fuscus, I have to say that I have HAD it with this month. Normally I start complaining about February around mid-January, and continue on every day until people start avoiding me. This year, I thought I could rise above it. I tried thinking positively. I tried reading Carl Jung and Viktor Frankl to address my existential crisis. Last night I was up late listening to Jordan Peterson, and I thought I was doing pretty well.

But this morning, after coming out to a car completely encased in ice (not exaggerating), after seeing the sky the same color as the ground (greyish white) YET AGAIN, and after some other crap that I won’t go on about, I’m done. February just sucks. It’s not me, it’s you, February.

So where did February come from?

Since I sat down intending to write about the very nice Latin word fuscus, I thought maybe I’d look up the origin of the word February and see if there was some Latin that could help make me feel better. And there was! So I’m sharing what I found in the hopes that it may help others who have February issues.

February is usually said to be derived from the Latin februum, meaning anything that purifies or consecrates. This doesn’t fit my view of this month, but whatever. According to a prominent Roman grammarian (what a cool job, seriously) named Censorinus, who wrote De Die Natali (The Birthday Book) in 238 AD, there were tons of februamenta (rites of purification) going on in Rome during this time of the calendar year. Part of the purification was agricultural (clearing away dead stuff and getting the fields ready for planting). But it wasn’t just fields – houses, material items, and even the Romans themselves were februa (purified) in different ways, using different rites.

Wait, why all the purification?

In Roman tradition, February was originally the last month of the year, and, according to Ovid, it was “consecrated to the shades of the dead.” So along with acts of propitiation (appeasement, I had to look it up too), there were acts of purification to protect the living from evil spirits and also to banish the spirits at the end of the year so that the new year could begin in purity.

The image above is a drawing of the month of February from a fourth century calendar. The caption describes how to placate the ghosts that roam the earth in February. Okay – keeping angry ghosts from haunting the living – now we’re getting somewhere.

There must be something better, though.

Yes, there is. Some sources suggest that February actually comes from feber, a word which the Romans used to describe lamentation. YES! That’s it. I KNEW there had to be something in the name of this miserable month that reflected its true nature. Okay, the Romans were lamenting their deceased. But still. It fits. For the rest of the month, I’m going to say Lamentation instead of February and see if anyone notices.

Okay, back to fuscus.

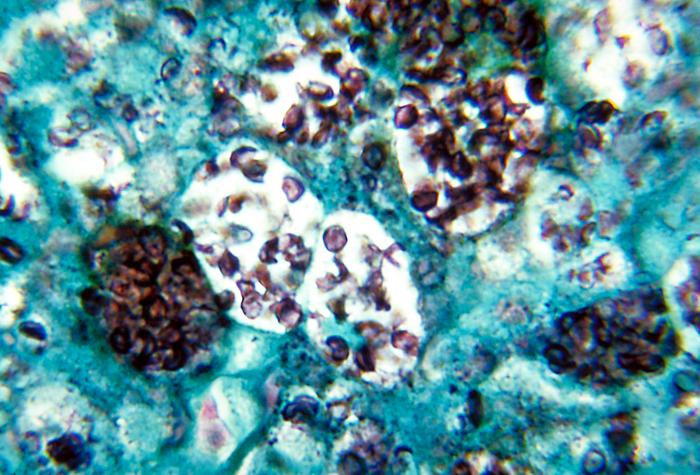

For those of you brave enough to read this far, here’s a happy thing to offset all the misery. As you may know, there are a bunch of pigments you can see sometimes in tissues. One of them is called lipofuscin. It’s known as the wear-and-tear pigment, because it accumulates with age. Lipofuscin is composed of a bunch of lipids and proteins and has a yellow-brown appearance. It has no clinical significance – but you need to know it exists so you don’t confuse it with something else yellow-brown, like hemosiderin.

Here’s the good part. The first half of lipofuscin makes sense, since it’s composed partly of lipids. The second half is derived from the Latin word fuscus, which means dingy, brown, or dark – great Latin word choice, since lipofuscin has a dingy, brown appearance. So that’s why “obfuscate” means “to make unclear or obscure.” And it may be where we got the word “dusk” (from Middle English dosk, which came from Old English dox, which probably came from our Latin hero fuscus).

This is the weird kind of thing that makes me happy. I have no idea why finding the Latin connection between two seemingly unrelated words should make me happy in such disproportionate measure – or happy at all – but it does.

In this month of Lamentation, I’ll take happiness where I can get it.

When cells undergo apoptosis, they also show a lot of different morphologic features. Overall, apoptotic cells appear shrunken, with really dense, dark, eosinophilic cytoplasm, and the chromatin in the nucleus aggregates into a dense mass which can fragment. Here’s a photo from Robbins showing an apoptotic cell:

When cells undergo apoptosis, they also show a lot of different morphologic features. Overall, apoptotic cells appear shrunken, with really dense, dark, eosinophilic cytoplasm, and the chromatin in the nucleus aggregates into a dense mass which can fragment. Here’s a photo from Robbins showing an apoptotic cell:

Q. I was reviewing for boards and had a question about blood types and pregnancy.

Q. I was reviewing for boards and had a question about blood types and pregnancy.

Recent Comments